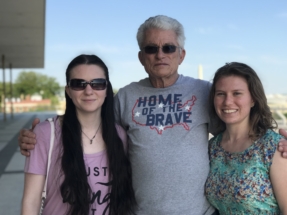

My Grandfather, My Hero

by Savanna Strott

Edward Ganey, my grandfather, served in the United States Air Force for 30 years, and those 30 years of service were far from the military stories of valor and sacrifice we often hear. Edward, who goes by “Ed” with friends and “Papa” with me, didn’t save the day or make a crucial decision. He never fought; he worked behind the scenes. And when I asked him why he joined on October 22, 1962—right in the middle of the Cuban missile crisis—it wasn’t a passionate cry for country, but rather an opportunity to fund his education in electronics and avoid a draft everyone expected. He initially planned on staying for four years and going to work in the private sector, but after four years of working in various electronic communications, he reenlisted to pursue a more in-depth education on heavy ground radars. When the next four years were over, he had a wife and family and based the decision again on practicalities. “The military is a lifestyle, and we liked the lifestyle,” and that’s why he stayed for 30 years, he told me.

Edward Ganey, my grandfather, served in the United States Air Force for 30 years, and those 30 years of service were far from the military stories of valor and sacrifice we often hear. Edward, who goes by “Ed” with friends and “Papa” with me, didn’t save the day or make a crucial decision. He never fought; he worked behind the scenes. And when I asked him why he joined on October 22, 1962—right in the middle of the Cuban missile crisis—it wasn’t a passionate cry for country, but rather an opportunity to fund his education in electronics and avoid a draft everyone expected. He initially planned on staying for four years and going to work in the private sector, but after four years of working in various electronic communications, he reenlisted to pursue a more in-depth education on heavy ground radars. When the next four years were over, he had a wife and family and based the decision again on practicalities. “The military is a lifestyle, and we liked the lifestyle,” and that’s why he stayed for 30 years, he told me.

While that 30 years is 22.5 years longer than the peak average career for enlisted personnel and sounds sublime, it never left that impression on my grandfather or my family. My mother, born in his 10th year of service, told me “I never thought Dad was a big deal. That was my life. It didn’t seem like anything exciting, anything special.” My siblings and I grew up knowing that my grandfather was a veteran and told him “Thank you” every veteran’s day, but it never seemed very riveting to any of us either. When other people hear of my grandfather’s 30 years of service, they’re impressed as their heads likely imagine 30 years of chasing the enemy or fiercely commanding battalions. While that might be the stories the media highlights, it’s not the story of Ed.

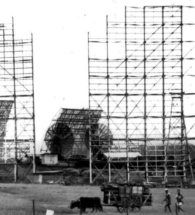

Instead, my grandfather’s story is divided between four rudimentary jobs: electronic communications, radar repair and maintenance, metrology at the Precision Measurement Equipment Laboratory (PMEL), and financial management. Obviously, these careers didn’t provide many opportunities for the action or heroism we usually see in featured military stories, but they did take my grandfather to some amazing places. He worked internationally in the Philippines, Vietnam, Thailand, Iran, and the Azores Islands off Portugal. These fascinating places are the setting to most of the colorful factoids of my grandfather’s career. His favorite of these being “Big John”—the 12-foot, 6-inch thick boa constrictor found on the radar site he was setting up in Ca Mau, Vietnam in ’66. Everyone on site oohed and awed at his size and took him to another site to mate with a boa constrictor there. “Well, Big John got pregnant,” my grandfather says as his punchline. “So Big John was not Big John—he was Big Jane!”

But the fun facts and alluring places are only snapshots of my grandfather’s 30 years. His careers, however mundane they may be, are really the core of his story. Out of those, the only room for excitement was his classified assignment in Iran from 1970-1972. With that, at least, you can let your imagination wander. My family would give humorous speculations and pleads to Papa’s poker face and sealed lips, barriers that weren’t technically necessary as the assignment was declassified many years ago. Only for the purpose of my journalistic endeavors has he decided to reveal the assignment. Through text, for the purposes of exact wording and no follow-up questions, he told me he worked as an “electronic technician operating equipment that detected nuclear events.” Of course, history will tell you that the nuclear relationship between the U.S. and Iran didn’t intensify during this time, so my grandfather’s tour in Iran ended and my family went to Lowry Air Force Base in Colorado where my grandfather did repair work on electronical equipment until ‘75. Anticlimactic, I know, but it’s the Edward Ganey truth.

When I mentioned the lack of excitement in Papa’s story to my grandmother, she told me that if I wanted someone exciting, I should have interviewed The Hulk. “Papa is kinda dry,” she said, telling me something I already knew. “That’s who Papa is.” She’s right—that’s just who my Papa is. The work he’s done isn’t necessarily captivating to most people, but the work is necessary. For instance, his time in the Precision Measurement Equipment Laboratory (PMEL) is probably one of the most dry and tedious careers you never knew the military offered. He worked in metrology—that’s right, they even have an “ology” for measurement—from 1976 to 1990 and ensured that tools like pressure gages and micrometers were giving accurate readings. The real-world example of PMEL work my grandfather gave me was with a gas pump. When you pump 5.00 gallons of gas into your car, how do you know you’re getting 5.00 gallons and not 4.50 or 5.27 gallons? You probably don’t even think about it, but a person comes and certifies that each pump dispenses the amount you paid for.

My grandfather was that person in PMEL. That process of ensuring accuracy with instruments was very tedious and required specific circumstances for each calibration. For example, the micrometer, which measures thickness, had to sit in a “cold room” of 68˚F (±1˚F) with a gauge block, a metal block of published thickness, for a defined amount of hours. This allowed the metal of the micrometer and the gauge block to contract and expand the same amount. Only after that time would my grandfather be able to measure the gauge block down to mere fractions of an inch with the micrometer. If the micrometer measurement was out of tolerance, it was adjusted and went through the testing process again.

My grandfather was that person in PMEL. That process of ensuring accuracy with instruments was very tedious and required specific circumstances for each calibration. For example, the micrometer, which measures thickness, had to sit in a “cold room” of 68˚F (±1˚F) with a gauge block, a metal block of published thickness, for a defined amount of hours. This allowed the metal of the micrometer and the gauge block to contract and expand the same amount. Only after that time would my grandfather be able to measure the gauge block down to mere fractions of an inch with the micrometer. If the micrometer measurement was out of tolerance, it was adjusted and went through the testing process again.

As you can see, it was a very meticulous job that was perfect for my grandfather, a very meticulous guy. It’s who he is. It’s why he was patient enough to sort a whole bag of M&M’S by color, so my grandmother could put a rainbow on my little sister’s Care Bear cake. And his meticulous nature is what made him great at his job. He rose from a technician in PMEL in 1976 to an assistant lab chief in 1980 to managing his own lab as lab chief in four different PMELs from ’81 to ’90. In 1989 he got promoted to Chief Master Sergeant (E-9): the highest of the Air Force ranks for enlisted personnel which only one percent can hold at a time.

This success came partly from his character and partly from his work ethic that was motivated by his passion for his job. For example, 1968 was the year my grandfather got married while also going to radar school. In recounting this, he told me, “I got a ‘two-for-one’: I got a lovely wife and nine months of electronics training,” showing that to him, learning about radars was right on par with his marriage. He held his career in this high esteem for all of his 30 years often bringing work home and studying the material to make it to the next rank. And if there’s any question left about how much he liked his “boring” job, he had “PMEL” as his customized license plate for his last two years in Alaska.

My grandfather’s passion for his work is important. A mistake in calibration could have led to a flaw in the manufacturing of a plane and a possibly fatal repercussion for the pilot. Even those fractions of an inch, seemingly negligible details, are critical. I witnessed how sloppy work in the fundamental part of a process snowballed to negative outcomes when I did high-school-level, PMEL-like work in experiments in science class. I rushed through this stage that I found incredibly boring and consequently, my results were often imprecise or full on wonky. “We have to have people who have passion about things that are boring and dry to the rest of us,” my mom told me. “We don’t care about it, but for the pilot, it’s life-or-death.”

But even when it’s not life-or-death, the outcomes of mundane tasks usually affect us every day without us realizing it. Upon being chosen by the base commander at Nellis Air Force Base in Las Vegas to be his resource advisor in 1990, my grandfather indirectly started making lots of decisions that affected the whole base. Managing money and working on the budget is difficult and monotonous, but it has important and extensive implications. According to my grandmother, my grandfather’s decisions had a positive impact—everyone on base had toilet paper.

“Believe me, in those days, when they were trying to cut back in the late 80s and 90s, the military was going through such a financial struggle that they would spend money on plane parts and those kinds of things, so then they wouldn’t have enough money for toilet paper. But Papa figured out that when you have money, you buy lots of toilet paper, and when you don’t have enough money for plane parts and stuff, Congress will find the money for parts of the plane. Congress ain’t gonna find any money for toilet paper, but you bet they will for the plane parts.”

So there you have it, Edward Ganey—meticulous master and toilet paper hero. Although it was a career that lacked action or drama or glamor, it was a career filled with dedication and a quiet passion for dry yet vital work. And there are many veterans with careers just like my grandpa. Veterans that, as my mom says, are “Good ole fashion people that do their job every day and don’t complain or don’t ask for ‘thanks.’ ” While they may never get a movie about them, these men and women serving their country in non-combat roles actually make up 80 percent of the Department of Defense’s more than three million employees, and most of them do not have stories that society typically honors. “There’s nothing exciting, no life-or-death moments,” my mom told me, “but the people behind the scenes are the ones who create those moments.” Veterans with stories of bravery and courage always deserve to be honored, but veterans like my grandfather who do the behind-the-scenes work also deserve to be honored with reverence and gratitude. So thank you, Papa, and all veterans for the quiet and unnoticed work you did for our country.

Savanna Strott is a sophomore at American University in Washington D.C.

Savanna Strott is a sophomore at American University in Washington D.C.

Savanna is majoring in Journalism with a minor in Creative Writing and Spanish.

Voice of the Vet is proud to present Savanna’s heartfelt tribute to her grandfather, Edward “PaPa” Ganey.

We thank Savanna Strott for here fantastic tribute and we thank CMSGT Edward Ganey for his service to our country!